Introduction

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

500 million**.

This is a (very rough) estimate of the number of comics (of all kinds) read in the world at least monthly. 37% of people in the USA read comics at least monthly. 46% of South Koreans read comics at least weekly. 50% of teenagers in France read Manga. The global market for comics in 2019 was estimated at almost $US17 billion and is expected to grow. You get the idea.

(**Calculated by me from statistics on rates of comics readership by country multiplied by the total populations of North America, Europe, Japan, and South Korea. This leaves out India, which has a strong comic interest but little data on readership rates.)

In other words, a lot of people read comics. This presents a great opportunity for scientists, practitioners, and activists in the environment and social practice to share, in collaboration with comic artists, important stories to more people. If they can tell good stories.

Around the world, we continue to struggle with pervasive and insidious challenges with racism, inequity, and environmental degradation. We need to talk and communicate more, certainly. And we need to do so in new ways that reach new people and in modes that reach them where they are, in forms that are attractive to them. As scientists and activists, we need to learn how to become better storytellers. Or at least hang out with better storytellers.

This is the inspiration for this roundtable. Can we tell better and more engaging stories about our environmental and social challenges? Can we widen the circle of people who read such stories and take action? Can we use them for education and engagement? Can they create good and entertaining and useful stories?

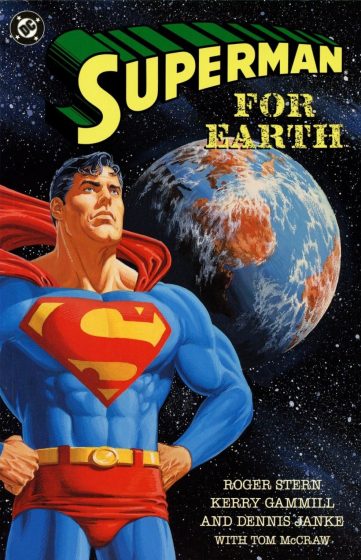

Although the comics landscape is dominated by superheroes doing classic superhero things, there is a growing movement of comics that have environmental and social justice aims. The Nature of Cities has launched a comic series called NBSComics—Nature to Save the World, a collaboration funded by NetworkNature and the European Commission on nature-based solutions for environmental challenges. Rewriting Extinction (with almost 2M readers on webtoon) is a remarkable series of comics with a community of over 300 artists, scientists, and storytellers. Le Monde Sans Fin (World Without End), by artist Christophe Blain and scientist Jean-Marc Jancovici, is a best-selling graphic novel exploring energy and climate change. As José Alaniz discusses in this round table, even Superman, in Superman for Earth, struggled against ecological degradation. There are an increasing number of examples.

Although the comics landscape is dominated by superheroes doing classic superhero things, there is a growing movement of comics that have environmental and social justice aims. The Nature of Cities has launched a comic series called NBSComics—Nature to Save the World, a collaboration funded by NetworkNature and the European Commission on nature-based solutions for environmental challenges. Rewriting Extinction (with almost 2M readers on webtoon) is a remarkable series of comics with a community of over 300 artists, scientists, and storytellers. Le Monde Sans Fin (World Without End), by artist Christophe Blain and scientist Jean-Marc Jancovici, is a best-selling graphic novel exploring energy and climate change. As José Alaniz discusses in this round table, even Superman, in Superman for Earth, struggled against ecological degradation. There are an increasing number of examples.

The pacing and format of comics allows people to contemplate and think between panels. And they can do so at a human-scale and in entertaining ways, engaging not just the heads of readers, but their hearts.

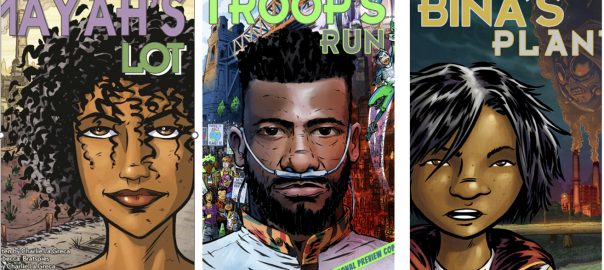

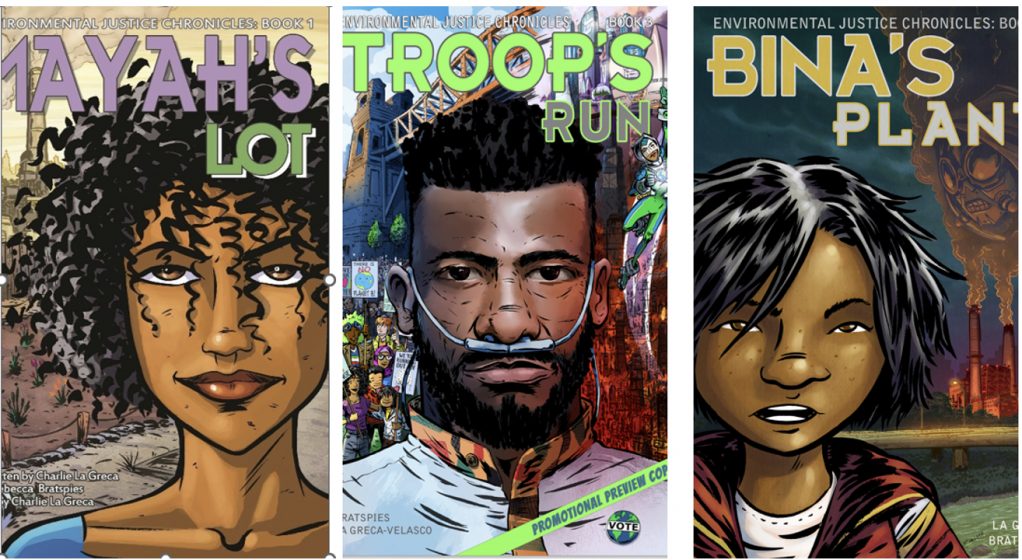

In social justice, likewise, there is an important history of comics that address racism, sexism, poverty, and environmental justice in ways that are frank, compelling, informative, and even entertaining. Charles Johnson in this roundtable discusses some of the history of this work. Remarkable examples include Candorville by Darrin Bell (the first black cartoonist to win a Pulitzer Prize) and the EJ (Environmental Justice) Chronicles, by Rebecca Bratspies and Charlie LaGreca (in this roundtable, and the banner image of at the top of this page).

But we need more.

Comics offer a unique and effective platform for addressing social and environmental challenges through storytelling. The combination of visuals and narratives in comics provides a dynamic and engaging medium to convey complex issues in a compelling manner. The visual nature of comics allows for the vivid representation of social and environmental challenges. Artists can depict the consequences of pollution, deforestation, or social inequality, bringing these issues to life and creating a lasting impact on readers. Their pacing allows people to contemplate and think between panels (unlike movies, which drive relentlessly forward).

And they can do so at a human-scale and in entertaining ways, engaging not just the heads of readers, but their hearts. They can capture the emotions and experiences of individuals affected by these challenges, fostering empathy and understanding.

Comics have the power to reach diverse audiences, including those who may not typically engage — or want to engage — with other forms of communication.

Comics are stories, typically including text, with pictures. It has always struck me that description — text + pictures = story — suggests ways for scientists, practitioners, and artists to collaborate. Scientists tend to be text-driven, too. What is a scientific journal article if not a story (text) with pictures (graphs)? Comics artists use tools with which scientists are at least vaguely familiar. That’s a a start for collaboration. Indeed, research suggests that people are less and less connected to scientific knowledge (Spiegel et al 2013). We need an additional path to science communication.

In other words, comics are big and full of potential to engage a lot of people with important stories of our shared challenges in social justice and the environment.

Let’s do more of it. But how? Read on.

References

Amy N. Spiegel, Julia McQuillan, Peter Halpin, Camillia Matuk, and Judy Diamond. 2013. Engaging Teenagers with Science Through Comics. Res Sci Educ. 43(6): 10.1007/s11165-013-9358-x.

Rebecca Bratspies

about the writer

Rebecca Bratspies

Rebecca Bratspies is a Professor at CUNY School of Law, where she is the founding director of the Center for Urban Environmental Reform. A scholar of environmental justice, and human rights, Rebecca has written scores of scholarly works including 4 books. Her most recent book is Naming Gotham: The Villains, Rogues, and Heroes Behind New York Place Names. With Charlie LaGreca-Velasco, Bratspies is co-creator of The Environmental Justice Chronicles: an award-winning series of comic books bringing environmental literacy to a new generation of environmental leaders. The ABA honored her with its 2021 Commitment to Diversity and Justice Award.

The Environmental Justice Chronicles succeeded far beyond our wildest dreams. We proved that comics can convey sophisticated legal/environmental information, while still being fun to read.

Comics are powerful advocacy

A decade ago, artist Charlie LaGreca-Velasco and I began the Environmental Justice Chronicles—a series of graphic novels set in Forestville, a fictional town that could be any place struggling with environmental injustice. Our goal: to build a new generation of environmental leaders focused on urban environmental justice.

The Environmental Justice Chronicles succeeded far beyond our wildest dreams. We proved that comics can convey sophisticated legal/environmental information, while still being fun to read. The books have been read in schools around the country, featured at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Museum, and made into a short video (in collaboration with Mt. Sinai.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v9ExRO_ETYk

The series began with a pun. LULU, the story’s villain, is an environmental acronym standing for “Locally-Undesirable Land Use.” LULUs are landfills, chemical factories, powerplants and other facilities that impose environmental and health risks on the surrounding community. LULUs are disproportionately sited in Black and brown communities. Naming our villain LULU intentionally evoked this unequal experience.

The series began with a pun. LULU, the story’s villain, is an environmental acronym standing for “Locally-Undesirable Land Use.” LULUs are landfills, chemical factories, powerplants and other facilities that impose environmental and health risks on the surrounding community. LULUs are disproportionately sited in Black and brown communities. Naming our villain LULU intentionally evoked this unequal experience.

In Mayah’s Lot, readers learn alongside Mayah as she organizes her neighborhood to thwart Green Solution’s scheme to site a toxic waste facility in her already overburdened community. With her leadership, the abandoned lot instead becomes a park, providing the community some desperately needed greenspace. The book stands alone as a story, but also provides valuable environmental justice lessons. It introduces readers to street science, basic administrative procedures, and effective community organizing.

Bina’s Plant revisits Forestville, this time telling a fictionalized version of a real environmental justice victory—the shuttering of the Poletti Power plant, one of the dirtiest power plants in the country. This book introduces more technical skills—how to intervene in a permitting decision and explores the relationship between legal advocacy, negotiation, and community mobilization.

Troop’s Run has our heroes entering Forestville’s electoral politics, running on a climate justice platform and facing off against fossil fuel special interests. The park they created in Book 1 becomes a rallying point for their climate advocacy.

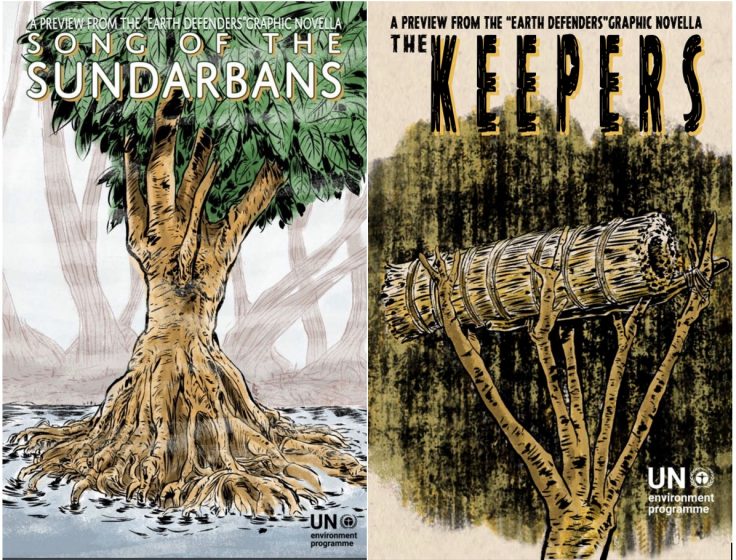

Our latest collaboration, The Earth Defenders raises awareness about the plight of environmental defenders around the world. The chapters span the globe, depicting brave environmental activists and the dangers they face as they invoke their human right to a healthy environment and defend their forests, water, land, and air. All these stories are drawn from real life. We work closely with the environmental defenders to make sure our comics are appropriate and respectful. Our mission is to amplify their stories rather than invent our own.

The Keepers tells the story of Kenya’s Sengwer People, forest dwellers being evicted from their traditional territory so their lands can become conservation lands.

Song of the Sunderbans depicts the grassroots resistance to Bangladesh’s decision to build an enormous coal-fired power plant in the Sunderbans—the largest intact mangrove forest in Asia.

The Prey Lang Patrollers, describes how Cambodia’s indigenous Kuy people have organized themselves into forest patrols to combat illegal logging in the Prey Lang forest. (coming soon). The fourth story (under development) is set in Colombia and tell of Afro-Colombian women being displaced in the name of “development.”

Our goal: to raise awareness about the dangers Environmental Defenders face, and to make sure that protecting environmental rights is on the agenda of every international conference discussing human rights or environmental protection.

Deianira D’Antoni

about the writer

Deianira D'Antoni

Deianira is an architect and illustrator specialising in communication and visual arts. She pursues the idea that the architect is not only a designer of buildings but an “organizer of thoughts and a social innovator”, who should be able to steer the common consciousness, raising awareness and inspiring it through his communication skills. Motivated by this sense of responsibility, she deepened her knowledge with a master’s degree in Milan on sustainability issues and an advanced training course in communication and marketing for architecture in Bologna.

In comics, a confidential relationship is established between the protagonist and the reader, a dialogue that stimulates creativity and prompts the reader to develop critical thinking, to reflect and open up to new and different perspectives.

When we talk about environmental and social challenges whose impacts are influenced by and affect an entire community, triggering virtuous behaviors at the small scale would allow for small, diffuse contributions with large, global impact. But how can we trigger positive and lasting change in the behavior and actions of a society saturated with media noise and information overcrowding?

The scientific and technical communities can play an important role, providing the proper tools for society (including lay public) to understand issues, read through massive amounts of data, and sift through effective solutions to undertake. A common awareness can be therefore promoted through the transfer of appropriate knowledge that can also initiate a process of raising awareness of social and environmental issues. The medium and language by which we decide to disseminate them must be well-screened to implement effective communication at multiple levels.

It is clear, however, that communicating complex issues to the general public is no small matter. In fact, the risk is to create a disparity in the dissemination of knowledge. But how can we find a linguistic code to subvert this disparity and open a dialogue with society as a whole?

Comics make it possible to systematize technical and specialized language with storytelling to make the topics covered accessible to a wide audience. But comics are not only a communication tool; in fact, in recent years several researchers have tested and analyzed their potential in the educational field. Comics fall into the category of multimodal messages because they combine verbal and visual stimuli. Multimedia messages increase arousal, focus attention, and enhance learning (Rosegard and Wilson, 2013, p. 7).

Since storytelling allows messages to be conveyed in an evocative manner, through metaphors, analogies, and symbolism in a continuous succession of meanings and signifiers, comics require the reader to make an effort to interpretation, invite them to participate, and make the communication process interactive. This is due to the fact that comics have wider margins than a text and thus leave room for interpretations arising from personal experiences and related to themes not directly expressed.

Comics creator Scott McCloud talks about this: between panels, the reader must take a position to “fill in” the progression of gaps between panels. In comics, a confidential relationship is established between the protagonist and the reader, a dialogue that stimulates creativity and prompts the reader to develop critical thinking, to reflect, and open up to new and different perspectives.

For years I have been seeking a synergy between the spheres of art and communication and the spheres of strategic planning and sustainability, with the aim of raising awareness of the issues of climate change, ecological transition, and spatial justice. This synergy would emphasize the need for a shared commitment to contributing to an environmentally and socially sustainable future. Comics is not the only method to achieve this goal, but it presents an interesting opportunity. It makes it possible to combine the “top-down” approach of the cartoonist who, starting from complex information, simplifies it by distributing it along the narration to allow the reader to orient himself; to the “bottom-up” approach of the reader who, starting from his own perception and basic knowledge, gradually immerses himself, through images and narration, in the complexity of the theme.

We could define comics as a democratic communication tool that can speak to the totality of the community, always being understandable even to less experienced readers and different age groups. The emotional drive comics is capable of generating, leveraging in the curiosity, allows to engage, inspire, and translate into the action of many, eventually triggering real change.

Besides… I’ve already tested it… a Talking Fox can explain, better than I could in words, to my little cousin, what we are capable of doing by committing all together to the environment and society!

References

Communicating Research through Comics: Transportation and Land Development | National Institute for Transportation and Communities (no date). Available at: https://nitc.trec.pdx.edu/news/communicating-research-through-comics-transportation-and-land-development.

Wylie, C.D. and Neeley, K.A. (2016) Learning Out Loud (LOL): How Comics Can Develop the Communication and Critical Thinking Abilities of Engineering Students. Available at: https://doi.org/10.18260/p.25542.

Patrick M. Lydon

about the writer

Patrick M. Lydon

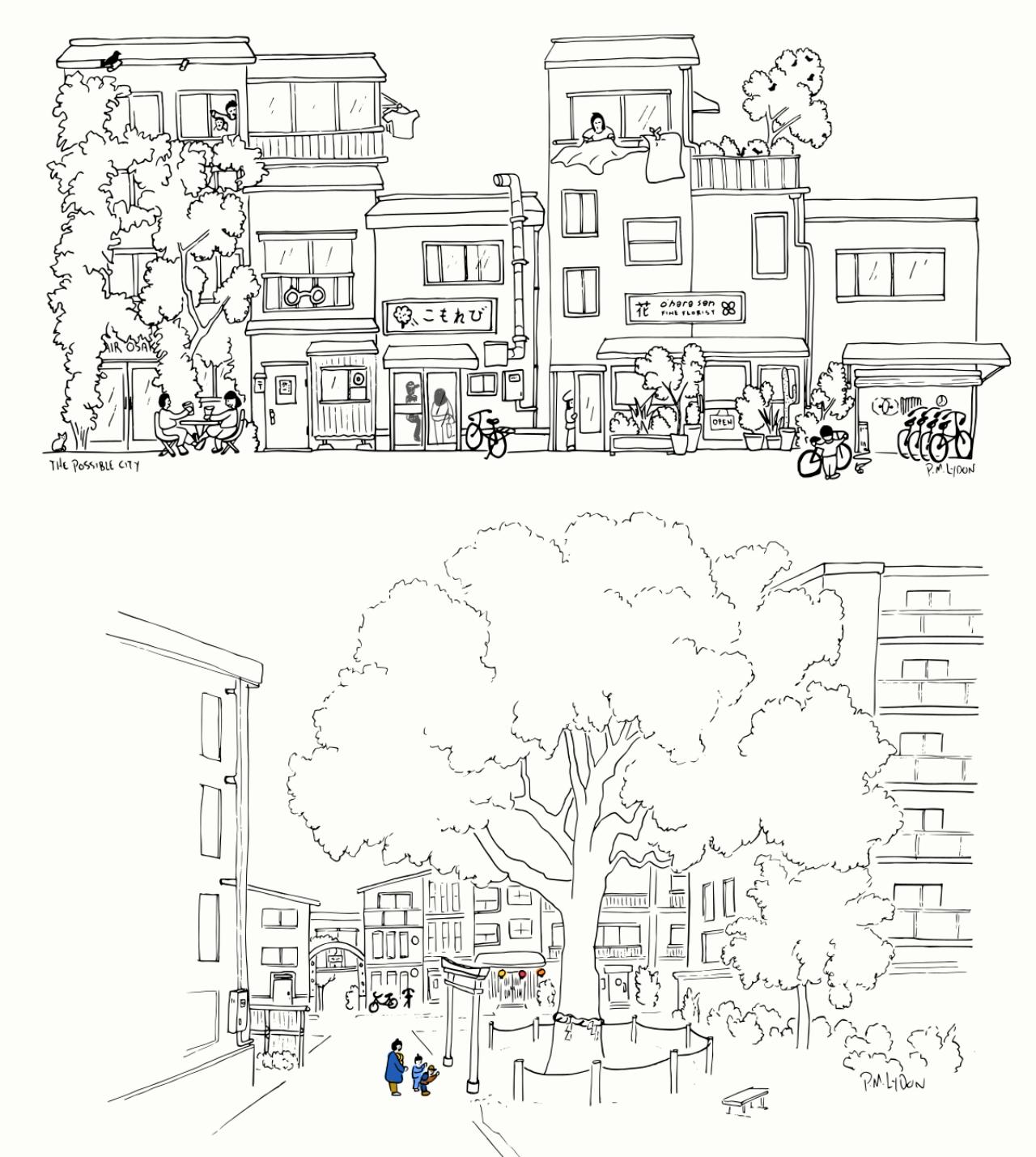

An American ecological writer and artist based in East Asia, Patrick uses story and community-based actions to help us rediscover our roles as ecological beings. He writes a weekly column called The Possible City, and is an arts editor here at The Nature of Cities.

Stories matter. Our democracy, our money, our relationships with nature, all of these are at their most basic level, stories. A culture that inherently inflicts wounds upon itself and its environment then, is doing so precisely because of its stories. The potential of NBS Comics is in its understanding, that we should do all that we can to tell better stories, together, not only as a human family, but as a part of nature.

If one wants to shift the way the world works, what they need first, is a good story.

Stories are so powerful, everything about our cultures and the ways that we live, are built upon them. Narratives shape our very reality, and without stories to make sense of this Earth and Universe and our place here, we would suddenly find it immensely difficult to function as individuals, let alone as a society.

Forget that meager Cartesian label of humans as thinking beings then, we might do better to call ourselves storytelling beings.

But how wide does this powerful realm of story actually reach?

Our democracy, for example, is not merely a system of governance. It is a powerful story that articulates ideals of equality, participation, and representation. The belief in this story is what enables democratic processes and institutions to function.

Similarly, money functions as a symbolic system of exchange and value, but its worth is derived from the story that a piece of paper or a digital record is valuable. Without a shared belief in this story, there is no value in money.

Just as well, our individual and cultural relationships with nature are stories too; these stories position ourselves, our cities, and our industries in relation to the rest of this nature. A culture that inherently inflicts wounds upon itself and its environment then, is doing so precisely because of its stories, and more specifically, the position in which these stories place humans — above, below, or within — the context of nature.

But there are other stories that we might not be so familiar with; stories like those of NBS that tell us, yes, we are living beings who have important roles within a living world that includes far more than just humans. The fact that these stories exist, and that they have successfully informed ecologically sound ways of being, means that the stories we tell matter far more than we usually give them credit for.

A few years ago I began an illustrated series called The Possible City. The series is an ongoing exploration based on these kinds of ideas. Stories matter. Many of our current cultural stories obviously inform habits that are not very beneficial to people and the environment. We need more compelling stories that resonate with the world that we think is possible.

But the matter of how we go about it is important, too.

The power of the NBS Comics project is that it it understands this: if stories are the foundations of our cultures, we should do all that we can to tell better stories, together. We should tell better stories that combine creative insights with both traditional and scientific knowledge, better stories about the world we should live in, not the one we currently inhabit. Like a FRIEC, we should also write, draw, paint, sing, perform and share these better stories, of what our human family might become if we take our proper seat at the table with the rest of nature, and listen. Most of all, we must do it, as the good Dr. David Maddox often says, across disciplines and ways of knowing. We need more projects that explore such radical transdisciplinarity, not only within human species, but all species.

NBS is too beautiful a concept to sit alone in the realm of data and statistics. It deserves a narrative revolution, one that can propel it from being a collection of definitions, to a completely new way of seeing and being.

Midori Yajima and Cecilia de Sanctis

about the writer

Midori Yajima

Midori Yajima is an illustrator and early career researcher in the natural sciences. Midori is visiting researcher at Trinity College Dublin and specialises in ecology and plant ecology, using traditional and mixed media for sciart and personal projects.

about the writer

Cecilia de Sanctis

Cecilia de Sanctis is an illustrator and early career researcher in the natural sciences. She specialises in biodiversity conservation and monitoring and is a professional illustrator, her work featuring in NGOs, international organisation such as IUCN, and science communication projects.

We live in a time when too many people see scientists as distant figures, giving advice from the top of their ivory tower. Engaging with stories can break that wall, and bring the discussion even beyond, by making it accessible, relatable, and maybe even more participatory. Still, it is right within the message that challenges hide.

Visual storytelling can definitely be a powerful tool for communication. It is able to harness complex themes in an engaging way, it sticks to the memory, or can even trigger emotional responses, rooting the understanding of something beyond the usual means used for science communication. We live in a historical time when even though more and more energy is spent in communication, too many people still see scientists as distant figures, giving advice from the top of their ivory tower. Engaging with stories can break that wall, and bring the discussion even beyond, by making it accessible, relatable, and maybe even more participatory. By opening a theme to a diverse audience, the potential of planting seeds of change just escalates, from simply sparking reflection to scaling up ideas and solutions to a greater scale, as big as the audience it reaches. If few informed (and determined) people can make a difference in a community, what could happen if the pool of people gets bigger? Bringing the discussion outside the usual set of people, means also bringing diversity to the ideas that can be generated, if the message is well delivered.

Still, it is right within the message that challenges hide. It would be important to find a narrative that does not hyper-simplify concepts. Presenting a silver bullet explanation is great for delivering a message, but what happens when facts diverge from that? Especially as with social-ecological dynamics, where reality is multifaceted. After all, the mistrust that has been rising towards scientists shouldn’t all be blamed on the public.

Another challenge closely related is for the scientist to face: deconstructing our ego. It is unlikely that readers will engage if the story makes them feel silly. How to shape our communication with empathy? Of course, this code switching is not easy at all for someone who dedicates so much time into a completely different dimension. But it is a direction worth exploring.

Last but not least is how to build the visual storytelling itself. Even though comics are great, there is a far greater constellation of visual means that is there available to use. No means is naturally best tailored, but the discussion often revolves around building linear stories, while sometimes this constraints complexity. Even a single image, or an abstract piece can inspire as much, depending on the audience, synthesising and still portraying a concept, just through a different lens, stimulating a different part of our brain.

So it is a matter of balance: understanding, completeness, depth in a continuous research for engaging with others in a meaningful way.

Mike Rosen

about the writer

Mike Rosen

Michael Rosen’s passion for comics began when he was 11, waned at 14, and reignited at 29. Michael edited the graphic novel Oil and Water, written by Steve Duin, drawn by Shannon Wheeler (Fantagraphics Books). He co-edited three comics on COVID by Shannon Wheeler and produced by NW Disability Support for the Oregon Health Authority (over 300,000 copies distributed). He has a PhD in Environmental Science and Engineering and 30 years of management experience with local and state government programs in natural resources. He is board chair for the NW Museum of Cartoon Arts. He resides in Portland, Oregon with his wife Terri.

Environmental and social justice aims do not have to be solely represented in nonfiction comics. Plenty of fictional comics, even including those with superheroes, can and have advanced this work. These are fun, informative, and motivational too.

I do believe comics can help us advance solutions to our social and environmental challenges. I see these types of books more and more in local comics shops, bookstores, and libraries. They include graphic novels on climate change, mental and physical health, government reform, the state of our democracy, racial history, and LGBTQ issues. They are prominently displayed and readily available. As such, I see the market for them are growing.

Comics are an effective tool for education and engagement. During the pandemic, through a grant from the Oregon Health Authority (Oregon’s state health agency), I worked with the cartoonist and writer Shannon Wheeler and the nonprofit Northwest Disability Support to create COVID-19 educational comics. Over 300,000 comics, in English and Spanish, were distributed throughout Oregon. Nonprofits, medical service providers, and schools used these comics to educate children and adults on preventing COVID-19, the vaccine, and boosters. Three comics were produced and covered emerging issues as they arose. The comics were engaging and informative. The medium helped explain complex issues simply. And readers were drawn in by the humor and vibrant, colorful art. We also emphasized diversity in the way we represented characters. They were different ages, colors, and abilities. The overall approach was an alternative to dense and complex text. The people that read these comics were better informed and took actions to protect their health and the health of others.

Generally, I think visual storytelling has the advantage of engaging all levels of readers and especially helps younger audiences whose comprehension is improved with visual representation of the subject matter.

One way to grow this movement is by investing in these endeavors through grants. Public service messages that are complex can be simplified and the audience for the message expanded by visual storytelling. Whenever the opportunity arises, I encourage government agencies to invest in this approach to messaging. I’ve also encouraged environmental nonprofits to consider telling the story of the important work they do through comics and to approach government agencies, like the Oregon Health Authority, to fund this work.

Finally, environmental and social justice aims do not have to be solely represented in nonfiction comics. Plenty of fictional comics, even including those with superheroes, can and have advanced this work. Growing up, many of the traditional comics I read dealt with complex issues such as, drug use, social change, and environmental protection. These were fun, informative, and motivational.

Shannon Wheeler

about the writer

Shannon Wheeler

Shannon Wheeler, multiple Eisner Award winner, creator of Too Much Coffee Man, and contributor to various publications including the New Yorker, MAD Magazine, and The Onion. He lives on a volcano in Portland, OR with cats, chickens, and bees. He is easy to find, follow and like on various social media platforms. His website is tmcm.com. His many books are equally easy to find and purchase. Wheeler is currently working on a graphic novel project about his father’s commune.

Cartoons don’t do much. But comics changed me. It was MAD Magazine’s anti-establishment cartoons that inspired me to write and draw cartoons myself. The hatred for the lies from all directions steered me in better directions. I like to think that reading comics made me a better person.

Can comics change the world? No.

A cartoon about global warming is not going to solve our environmental crisis. Another cartoon about mass shootings is not going to change someone’s mind about the need for gun regulations. Cartoons don’t do much.

But comics changed me. At a very young age, MAD Magazine taught me that advertising was not to be trusted. I learned from their cartoons, if someone told you that they could solve your problems by selling you something, they were trying to sell you something. It was their anti-establishment cartoons that inspired me to write and draw cartoons myself. The hatred for the lies that came from salesmen, politicians, and corporate shills steered me from becoming one of those people myself. I like to think that reading comics made me a better person.

I drew a graphic novel about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill highlighting the profound effects of an environmental disaster on everyday people. I also turned the Mueller Report into a graphic novel as a way to make the information accessible and to counteract the political spin that dominated the public discourse. Did my work change anyone’s mind? I doubt it.

But with any luck my work touched a couple people, fostered some empathy, and educated a soul or two. If I helped someone from losing their soul to the ruthless economic machinery of our modern world in the same way I was helped, I’d call that a win.

So, sure. Comics can be a good thing.

Ivan Gajos

about the writer

Ivan Gajos

Ivan is a highly respected art director, photographer and film maker who has worked for a number of international design agencies in both the UK and Australia. His expertise encompasses a variety of contemporary and classic styles, though he is perhaps best known for his clean and functional approach to graphic design.

In order to engage ordinary people and inspire the next generation we need to go beyond traditional communication methods and embrace more creative storytelling. Comics have a superpower that makes them especially useful when communicating social and environmental challenges.

In a sector often characterised by overwhelming complexity, a constant barrage of information and public misinformation, effectively communicating social and environmental challenges has never been more important. Enter comics—a remarkable medium that can tackle complex themes, challenge preconceived ideas and engage readers with mature storytelling and thought-provoking narratives.

In order to engage ordinary people and inspire the next generation we need to go beyond traditional communication methods and embrace more creative storytelling. Comics have a superpower that makes them especially useful when communicating social and environmental challenges: comics can convey complex concepts in accessible and engaging ways. When used well, comics can educate, inspire, and trigger journeys of discovery without compromising scientific integrity.

Comic artists have a number of tools at their disposal to convey complex concepts whilst maintaining the delicate balance between accuracy and clarity. Through concise dialogue, vivid imagery, and visual metaphors, comics have the power to illuminate the most complex scientific concepts, transforming impenetrable jargon into a compelling and comprehensible story.

Comics can present multiple narratives on a single page—whether they be different timelines or concurrent events unfolding in parallel. While movies can achieve this with jump cuts, comics excel at conveying complex narrative ideas in a simple and more powerful manner. A single page, read panel by panel or viewed as a whole, can convey information, emotions, and ideas simultaneously through the interplay of visuals and text.

In the comic “Watchmen” by Alan Moore the story unfolds through a series of interconnected flashbacks, present-day events, and various character perspectives. This allows for a complex exploration of characters and their backstories encouraging the reader to piece together information to uncover the story. This mastery of visual storytelling sets comics apart from other media forms.

Unlike movies, comics can be read at a reader’s own pace. A reader can effortlessly rewind, pause or fast-forward in order to fully grasp a new concept or revisit a section that requires deeper understanding. By manipulating panel size, layout, and employing visual techniques such as transitions, artists can control the pacing and rhythm of the narrative. This level of control is unparalleled in other media forms, where timing is dictated by factors such as screen time and the experience is often more linear.

Comics also often invite readers to actively engage their imagination by leaving certain details open to interpretation. The limited visual information in each panel encourages readers to fill in the gaps and imagine the spaces between panels or the moments preceding and following depicted scenes.

The comic “Maus” by Art Spiegelman tells the story of the Holocaust, with Jews portrayed as mice and Nazis as cats. Spiegelman uses a minimalist art style and utilises visual metaphors, symbolism, and ambiguous imagery throughout the comic. By leaving certain details open to interpretation, “Maus” encourages readers to engage actively with the comic and draw their own conclusions. This interactive engagement fosters a deeper connection between the reader and the comic, immersing them in the story and allowing for a more personal and meaningful experience.

As the world becomes increasingly fast-paced and inundated with bite-sized information and clickbait articles, comics stand apart as an approachable medium for conveying complex ideas, inspiring readers, and engaging wildly diverse audiences. By embracing the transformative power of comics, we can make our work more accessible and engaging, and connect with readers on a deeper level, inspiring emotions, and creating art that is cherished.

David Haley

about the writer

David Haley

David makes art with ecology, to inquire and learn. He researches, publishes, and works internationally with ecosystems and their inhabitants, using images, poetic texts, walking and sculptural installations to generate dialogues that question climate change, species extinction, urban development, the nature of water transdisciplinarity and ecopedagogy for ‘capable futures’.

It’s time for diverse superheroes to story our planet into many futures beyond modernity’s monoculture, be they from Gotham City, Kolkata, or our own home towns.

Storying Our World

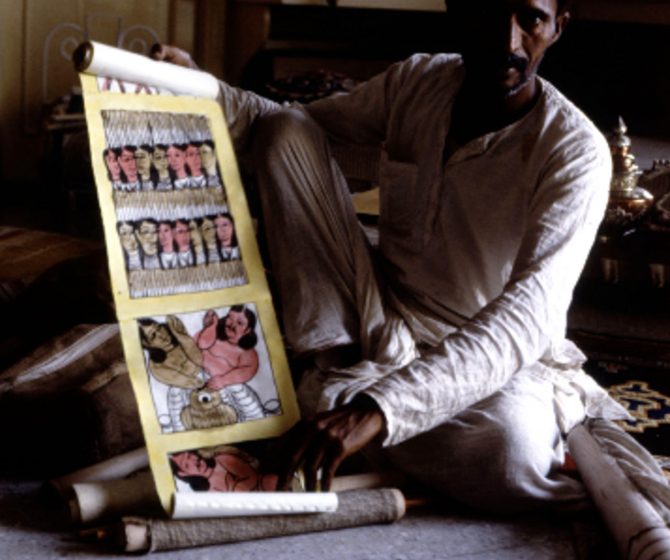

In 1985, in a crowded Kolkata spice market, a man cleared a space by chanting and then sat on the floor. From a large cotton sack, he pulled some scrolls. He continued to chant and the gathered crowd waited in anticipation while he decided which scroll to use. Eventually, he pulled a thread to release a scroll. He rocked up onto his haunches and chanted loudly as he unravelled the scroll, pointing to a hand-painted image. People in the audience (now six or eight deep) interacted as subsequent images were revealed. The sequence of images told the story of a man and his family having problems with people in his village, as the rains persisted to fall. Eventually, the man, his family, and his livestock were on top of a hill, while others drowned. The final frame of the story saw a helicopter fly in to save the man, his family and animals. This was a latter day rendering of Noah, with the ark transformed into a helicopter. Bengal is no stranger to flooding, but in 1985 few people knew about the climate emergency. They did know that deforestation in the foothills of the Himalayas was not a good thing and that floods were becoming more frequent and more devastating. Through his Bengali folk-style comic, this Phart storyteller/artist was effectively prophesying what the Rio Earth Summit made public in 1992.

As far as we know, people have storied (made and told stories) their world in words and pictures since Paleolithic times, over 47,000 years ago. The making and telling of stories, as one integral act is an important process to understanding the dynamic processes of neurological development and “fundamental culture” (Machado de Oliveria 2021, Morin 2006). This is how our belief systems are formed.

We may speculate that, orally, “In the beginning there was the Word…” and graphic pictures certainly predated written text, possibly accompanied by some forms of performance to celebrate the natural world, rights of passage and great events (Boal 2008). Then things changed irrevocably about 5,000 years ago with the Fertile Crescent / Cradle of Civilization, when people changed their agricultural and trading practices, became sedentary and invented cities. They also started to develop picture sequences that became text and by 3400 BC were being collected in city-state libraries, like that at Uruk in Sumaria.

We can then fast-track through Alexandria, Ancient Greece, Rome, China, the European Middle Ages and the invention of the mechanical printing press to comics of Europe, America and Japan of the 20th Century.

The important thing throughout this history was the story; a sequence of moments or incidents that in a linear or circular fashion make some sort of sense to tell us something. The combination of pictures and text, evokes two of our senses simultaneously. The form, the making and the telling, provide the means of creating and communicating that emerge as another thing. As the English artist, David Hockney repeated as a mantra in his film, A Day On The Grand Canal With The Emperor Of China, surface is illusion but so is depth: “The way we depict space determines what we do with it” (Hockney 1998). And comics generate their own space, or multiple spaces within each medium they appear. And as we know, “the most moral act of all is the creation of space for life to move onwards” (Pirsig 1993).

Not childish, but childlike, these multi-dimensional, multi-perspectival worldviews allow dreams to pass through what society and formal education teach us to believe is reality. They expand the possibilities of our ontological existence to experience pre-modernity understandings of being in the world. In this sense, they make way for the possibilities of humour, serious comedy, lampooning and the paradoxical insights of Trickster (Hyde 2008).

It’s time for diverse superheroes to story our planet into many futures beyond modernity’s monoculture, be they from Gotham City, Kolkata, or our own home towns.

References

Boal, Augusto. (2008) Theatre of the Oppressed (Get Political). Pluto Press, Sidmouth, England

Hockney, David (1998) dir. Haas, Phillip. Day on the Grand Canal With the Emperor of China. Milestone Films. https://milestonefilms.com/products/day-on-the-grand-canal-with-the-emperor-of-chinga (Accessed 30 January 2023)

Hyde, Lewis (2008), Trickster Makes This World: How Disruptive Imagination Creates Culture, Edinburgh: Canongate Books.

Machado de Oliveira, Vanessa (2021) Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism. North Atlantic Books, Berkley, California

Morin, Edgar. (2006) Restricted Complexity, General Complexity. http://cogprints.org/5217/1/Morin.pdf (Retrieved 27.02.18) p. 10.

Pirsig, Robert. M. (1993) Lila: An Inquiry Into Morals. Black Swan, London p.407

Marta Delas

about the writer

Marta Delas

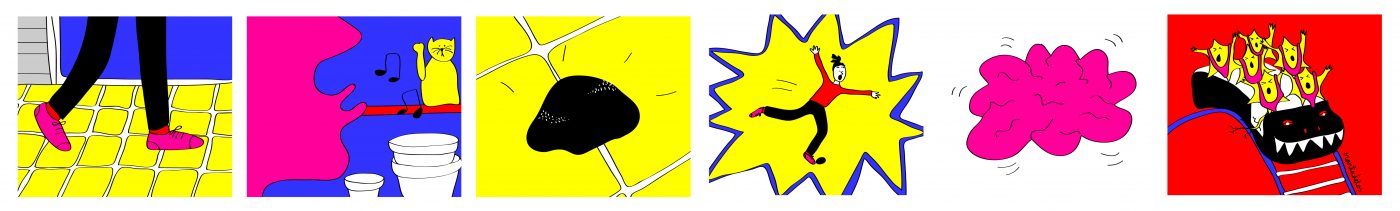

Marta Delas is a Spanish architect, illustrator, and videomaker. Concerned about urban planning and identity, her artwork engages with local projects and initiatives, giving support to neighbourhood networks. She has been involved in many community building art projects in Madrid, Vienna, Sao Paulo and now Barcelona. Her flashy coloured and fluid shaped language harbours a vindictive spirit, dressed with her experimental rallying cries whenever there is a chance. Together with comics and animations she is now building her own musical universe.

Reading a comic sounds more fun than reading an article or a textbook. Fun is a powerful tool. So is beauty. And emotional engagement. We can use all of these tools in a comic, creating stories full of knowledge.

If we are going to “save the world”, we have to think of new ways to communicate and engage wider audiences with knowledge. Why are there many researchers passionately working on finding solutions and better practices in order to face the challenges we have ahead as a society, while our policies are not taking this knowledge into account? There is an immense gap between knowledge and the public and there are not enough resources being used to solve this problem. It is key, for our democracies to work, that decision-making is guided by knowledge. So, it is urgent for us to think of effective ways to inform and give access to it.

Reading a comic sounds more fun than reading an article or a textbook. Fun is a powerful tool. So is beauty. And emotional engagement. We can use all of these tools in a comic, creating stories full of knowledge. Text and image combined are able to introduce a great complexity, allowing us to engage an audience with a character’s story at the same time as introducing other layers of information. The target audience can determine how we tackle a subject but it is important never to lose sight of the entertaining side of a comic. For these stories to reach a bigger number of people, they need to be able to be read for leisure. We know there is a wide audience for stories, Netflix series pop up constantly in our daily conversations. But watching a series is something we do for recreation, not necessarily to become informed.

We also need to acknowledge, even if we are analogical paper lovers, that nowadays communication is ruled by screens. Comic books need to continue to exist (please!) but it is fundamental that comics can be brought into a screen, and many already have. This makes them even a more powerful tool, being able to fit into mainstream platforms such as, for example, Instagram. Many comic writers have adapted their format to this platform, creating short comic trips with 10 images, the maximum number the platform allows to be published at the same time. This strategy is important: condensing information to what the public is used to. Communication has become quicker; attention spans have shrunk in the past years, and stories need to catch the reader’s attention rapidly, in order to ensure it doesn’t get “scrolled on”.

We also need to acknowledge, even if we are analogical paper lovers, that nowadays communication is ruled by screens. Comic books need to continue to exist (please!) but it is fundamental that comics can be brought into a screen, and many already have. This makes them even a more powerful tool, being able to fit into mainstream platforms such as, for example, Instagram. Many comic writers have adapted their format to this platform, creating short comic trips with 10 images, the maximum number the platform allows to be published at the same time. This strategy is important: condensing information to what the public is used to. Communication has become quicker; attention spans have shrunk in the past years, and stories need to catch the reader’s attention rapidly, in order to ensure it doesn’t get “scrolled on”.

The same way comics are a fantastic way to educate and engage, it is crucial that we explore other forms of communication too, that can help us raise awareness on important topics. Videos can be very useful in order to be shared in other popular social media platforms such as TikTok and YouTube. TikTok has over 1 billion monthly users worldwide, for example. It is essential that we recognize the potential of these platforms for educational purposes in order to get knowledge out of research institutions’ walls. There is a lot at stake.

Mark Russell

about the writer

Mark Russell

Mark Russell is an author and a GLAAD, Eisner, and Ringo award-winning writer of comic books. His titles include The Flintstones, Superman: Space Age, Second Coming, and Not All Robots, among many others.

Comics combine the best of the visual and text-based worlds, allowing people to read at their own rate, to stop and digest impactful moments as they occur, but also being a visual medium that can quickly convey information in a clear and immediate manner.

Yes, not only can comics help in advancing solutions to social and environmental challenges, they are uniquely qualified to do so.

Comics are an ideal medium for educating and inspiring activism for several reasons, which I will go into here, but the first and foremost being that as a medium that is both visual and textual, it works in much the same way the human brain does. In other visual media, like movies and television, the viewer is a passive observer, absorbing the information at the pace the director intended and with little time for digestion of what is being presented. The result being that, while accessible and easy to consume, much of the impact fails to take hold in the mind of the viewer because they are always having to focus on new incoming information. Printed media, like journalism and novels, lends itself well to pause and thoughtful analysis of what is being said, but it’s a good deal more laborious to consume and is not as accessible to a wide audience. Comics, on the other hand, combine the best of both worlds, allowing people to read at their own rate, to stop and digest impactful moments as they occur, but also being a visual medium that can convey information in a clear and immediate manner. This is why the 9/11 Commission printed their findings in graphic novel form. It was much easier to convey the engineering and architectural conclusions with drawings and images. And it was more accessible to a wider audience that didn’t have backgrounds in engineering and science.

And accessibility is perhaps the most important factor in any effort to educate people who are not a captive audience. It is a truism in media that if people can choose to be doing something else, they probably will. So in order to get people to willingly spend their limited time and attention on what you have to say, it helps to present it in a format they can quickly absorb and which has some immediate payoff, the way a good splash page or a panel with a high image-to-word ratio does. While this may be a gross simplification, in many cases, comics are to literature what a ten-minute YouTube video is to a two-hour documentary. While the documentary might be amazing, people are generally more willing to take a chance on the ten-minute video. Especially when it comes to younger audiences.

And this brings me to the third reason why I think comics are ideally suited to this mission. Their readership skews younger than other printed media. In any sort of social or political advocacy, I think it’s important to reach people while they’re still young, before identities and worldviews harden into stone. While our understanding of the world is molten and we are still sensitive to the pain of the world, this is when we need to learn about the impact we have on it. This is when we need most to feel like we are not merely passive observers, but active contributors to the future. And one of the reasons comics were created, and in particular why superhero comics were created, was to allow children, if only for a short time, to not feel like children. But to feel like they are the most powerful people in the world. And to think about what they would do to fix the world if, someday, they had the power.

Darren Fisher

about the writer

Darren Fisher

Dr. Darren Fisher makes comic-based explainers and illustrations, turning complex ideas and subjective experiences into visual communication with a twist. Some recent projects include book Illustrations emphasising the importance of workplace health and safety through a series of gritty and graphic depictions of disability, told straight from lived experience; and an animated story-reel informing about an EU-funded scientific project to provide the knowledge base needed to make the political goal of conserving 30% of Europe’s nature by 2030 reality. More recently Dr. Fisher created an animated comic shown at 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). He currently resides in Austria and volunteer as a drawing demonstrator and facilitator with SOS Kinderdorf, an independent, non-governmental organization that provides humanitarian assistance to children in need.

One of the things I love about comics is how simple they can be, and how low the bar is to entry is. More people telling their stories in this medium can only help to promote visual storytelling as a way to understand and talk about the great challenges we face in meaningful and impactful ways.

I feel like nowadays it’s not enough to just produce comics and put them online. You need to integrate with other media and embrace social media. This means creating reels for Instagram, motion comics for YouTube, discussing on Twitter, and continuing the conversations on podcasts and livestreams. Anything to promote the message further.

Comics can also embrace a transmedia approach, where you also need to access other media to get the full picture. Unless you’re one of the big publishers and producing comics with established mainstream characters, it’s going to be difficult to make an impact, regardless of the quality of your product. So, you need to think about all the different angles of promotion that are possible. We also might think about how the images from these comics and the storylines can be promoted at related events, for example, protest rallies, or included as part of relevant NGOs such as Greenpeace in their actions. Joining forces with like-minded initiatives to broaden the reach of comic-based visual storytelling is a win-win scenario. They get to lean into a bank of campaign-ready images, and we get to expand the reach of comic-based visual storytelling.

As for the stories themselves, you want to hear from as many different people as possible and be ready to publish outside your comfort zone or personal preference. Incorporate as many different styles as possible and be willing to take risks. Of course, you might offend someone by publishing unconventional comics outside the mainstream. But that’s okay, it’s all part of making an impact. You want a huge diversity of vectors to approach the issues from, across genre and voice. Stories should be told from deeply personal first-person perspectives and high-level narratives that give the lie of the land regarding the complexities of biodiversity and conservation, and everything in between. I think variety will help to give a lot more opportunities for resonating with a wide base of people, connecting on the frequency that works best be it emotional or cerebral, and invigorating some kind of meaningful response. We know comics can do this uniquely, provided people take the time to engage. So first you need to cut through the noise, pop up often enough on a multitude of different channels, and have enough choice of offerings that you increase the chances of connecting with people.

That only touches on the surface of curation and distribution. The practice of making is itself incredibly valuable as a way to better understand the world and ourselves. Running drawing and comics workshops where people work with artists to learn how to tell their own story of connection to nature, and how to share that story online, would be a powerful companion piece to your efforts. This would say loudly and clearly that comics are a democratised medium. One of the things I love about comics is how simple they can be, and how low the bar is to entry is. You put one picture next to another, add some text, maybe some symbols, and you’ve good some kind of a story starting to form. Everyone can tell their story in this way, basically any type of story they want, on any sort of subject matter. There’s no limit to budgets; anything you want to show is possible, provided you have the time. More people telling their stories in this medium, and more frequency of seeing comics language in a variety of contexts, can only help in the aim of promoting visual storytelling as a way to understand and talk about the great challenges we face in meaningful and impactful ways.

Joe Magee

about the writer

Joe Magee

Joe Magee is an award-winning artist, illustrator, and film maker. He has been a regular contributor of images to a range of international publications such as Libération, The Washington Post, The Guardian, Time Magazine, New York Times and Newsweek – having upwards of two thousand images published.

Through the process of sitting down with him and visualising his methods in the field using drawings and then photo-collages, I captured visually the solutions he was employing.

Comics can really help advance solutions for social and environmental challenges. When I began to illustrate my comic, The Sound of a River (which explores nature-based ways to prevent flooding in towns) in collaboration with flood management scientist Chris Uttley, I didn’t fully understand the work that Chris was doing. Through the process of sitting down with him and visualising his methods in the field using drawings and then photo-collages, I captured visually the solutions he was employing. Weaving these images and techniques into an engaging story about a young girl whose house floods meant that the whole concept, including the potential causes of, and solutions to, urban flooding could be delivered to readers in an almost subliminal way. All sorts of small details were incorporated into the images to give a richness around the subject.

My teenage daughter read the comic in about 5 minutes and I felt that she had understood the concept in a way that, maybe, just by reading some text about it might have been too dry, boring, and hard to comprehend. The images will have stayed in her head to help establish her awareness of the subject.

Chris Uttley

about the writer

Chris Uttley

Chris Uttley has been working for the protection and conservation of marine and freshwater habitats since his youth, working as both a practical ecologist and advising on conservation policy for aquatic ecosystems. For the last 9 years, Chris has worked at the cutting edge of nature-based solutions for climate adaptation and reducing flood risk, leading the Stroud valleys natural flood management project.

A comic can help people to visualise and hear about environmental problems and their solutions, in ways that cut through cultural expectations and norms to inform and entertain.

In summary, the answer is yes. Environmental problems are often complex and multi-faceted and don’t fit neatly into a good vs bad or straightforward paradigms. Even professionals sometimes struggle to articulate the problems in ways that everyone can understand. It can be even harder to visualise how we need things to change. That’s where storytelling and creative art can play a role and a comic is a great way of combining good art and good storytelling.

During the production of our comic, Joe Magee and I came up with the basic story very quickly, and I articulated what might be wrong with an engineered river, but explaining to Joe what the issues were and how to illustrate these, and how we want things to change was difficult and challenging. When I showed Joe photos of what a “Good” river looks like, he explained that he thought that was just “flooding” and not a healthy, well-functioning river occupying its natural floodplain. It shows that we are so used to existing in damaged and degraded ecosystems that when we are shown what “good” looks like, we think it looks wrong or a mistake, and damaged looks normal.

A comic can help people to visualise and hear about environmental problems and their solutions, in ways that cut through cultural expectations and norms to inform and entertain.

Jose Alaniz

about the writer

José Alaniz

José Alaniz, professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures and the Department of Cinema and Media Studies (adjunct) at the University of Washington, Seattle, has published three monographs, Komiks: Comic Art in Russia (University Press of Mississippi, 2010); Death, Disability and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond (UPM, 2014); and Resurrection: Comics in Post-Soviet Russia (OSU Press, 2022).

No less than Superman in “Superman for Earth” was not up to the task of solving the environmental crisis: a NIMBY protest objecting to the siting of a landfill; a new housing development in Smallville consuming farmland; or Lois expressing morality about having children in an overpopulated world. “There are no easy answers,” he concludes.

An auspicious attempt to redefine the superhero within the context of the Anthropocene’s complex systemic challenges (in the end showing up the genre’s in-built disadvantages for such a task) came in the guise of Roger Stern and Kerry Gammill’s Superman For Earth (1991).

This in-continuity DC one-shot shows the Man of Steel confronting the world’s pollution, deforestation, and mass extinction with super-powers. When they come up woefully short, the liberal bromides and late-capitalist “fixes” ring even more hollow. Still, the graphic novella effectively parlays a reader’s familiarity with the Superman mythos for an informative, fact-filled evocation of late-20th-century environmentalist angst.

The story opens with a discomfited Lois Lane telling fiancé Clark Kent about her research to prepare for an upcoming international ecology symposium which she will cover as a journalist: “… Acid rain, toxic waste, the greenhouse effect, species extinction […] we’ve done some terrible things to this world …” (n.p.). Superman notices some of these effects while flying about; we learn that Metropolis’ skies and Hob’s river have become noticeably dirtier since Perry White’s childhood and Superman’s arrival—instances of solastalgia.

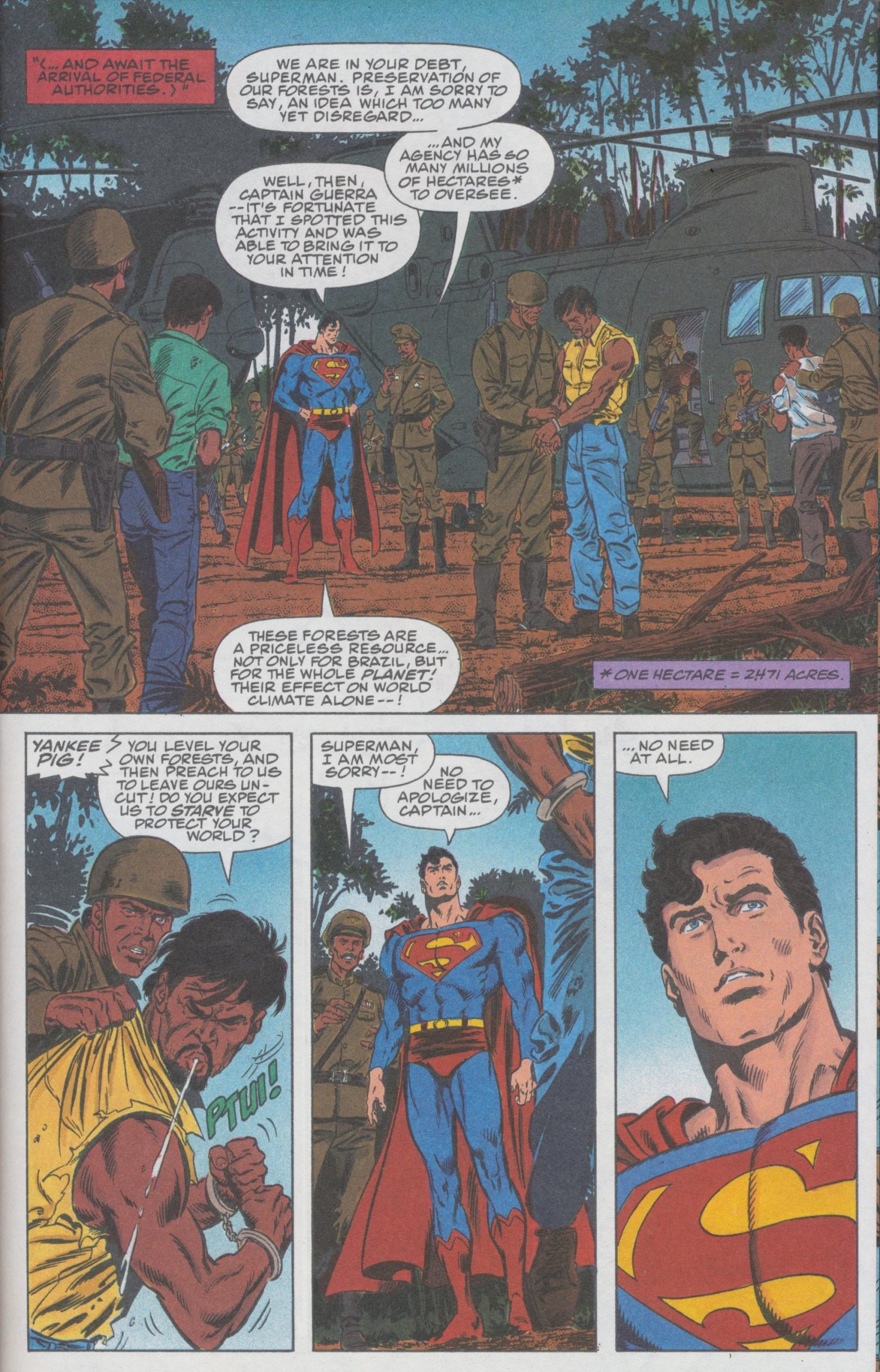

As he often does, Kal-El takes it upon himself to lend a hand. But the hero’s every attempt to address this crisis only reveals how multi-faceted and fathomless it really is. In addition, Superman’s efforts are all reactive: the FBI and EPA ask him to help foil a toxic oil ring, so he does; White complains about the polluted river, so Supes goes to sweep up garbage out of it; while doing that, he notices a leaking sewage pipe and seals it up; he spots illegal logging in the Amazon, so he stops it. “I don’t think I’ve ever spent so much time on any one task before,” he sighs.

As he often does, Kal-El takes it upon himself to lend a hand. But the hero’s every attempt to address this crisis only reveals how multi-faceted and fathomless it really is. In addition, Superman’s efforts are all reactive: the FBI and EPA ask him to help foil a toxic oil ring, so he does; White complains about the polluted river, so Supes goes to sweep up garbage out of it; while doing that, he notices a leaking sewage pipe and seals it up; he spots illegal logging in the Amazon, so he stops it. “I don’t think I’ve ever spent so much time on any one task before,” he sighs.

The problem is too big even for the Man of Tomorrow, who discovers that modern ways of life in the US lie at the root of the country’s environmental woes. For example, a scientific analysis shows that the partially-cleaned river carries innumerable chemical pollutants (it’s not just a matter of sunken old tires and shopping carts), while even a paper recycling facility leaks deadly dioxin. “I can assure you,” its director tells our hero, “our plant meets federal standards.”

Appalled as he is by the ubiquitous presence of that dangerous substance, even in milk cartons and diapers, Superman flies again and again into a wall of neoliberal business-as-usual. Frustrated, he grouses: “Mills in Sweden are already using a safer oxygen-bleaching process in their paper production. But American mills have been slower to change. Instead, they’ve argued that the dioxin levels are too low to be a health hazard.”

A scene in the Amazonian rainforest introduces still more complexity. It opens with a panoramic shot of dark-skinned loggers chainsawing and burning the trees as terrified animals flee. They are criminally clearing the land for a “great ranch”—presumably to pasture cattle for beef. Superman stops their operation cold; the federal authorities arrive to take the perpetrators into custody. Our hero lectures them (in Portuguese) with familiar platitudes about the rainforests as a “priceless resource” for their role in the planet’s climate and so on. But the logger foreman spits at his feet, saying, “Yankee pig! You level your own forests, and then preach to us to leave ours uncut! Do you expect us to starve to protect your world?”

As Lois responds when she hears of the incident: “The United States talks big about bettering the environment, but we set a wretched example, don’t we? We’re the most conspicuous consumers.”

The story continues in this vein, with Superman repeatedly shown as not up to the task of solving this crisis, whether at a NIMBY protest objecting to the siting of a landfill; a new housing development in Smallville which is consuming farmland (“Where are all the people coming from?” Ma Kent worries); or Lois expressing doubts about having children once she and Clark marry, referencing debates about the ethics of childbirth in the Anthropocene (he answers that his alien genes may make that issue moot). “It’s such a complicated problem,” he concludes. “There are no easy answers. I’m afraid that what is needed is a major change in the way we live—maybe even the way we think!”

He’s certainly right about that, but Superman’s failures here of course owe as much to the market’s approach to the genre as to any extratextual global state of affairs. In a deeply-rooted convention, mainstream superheroes do not forcibly impose their will on society as a whole, even for its own good (as they perceive it)—if they do, they’ve become villains like Watchmen’s Adrian Veidt. So the hero must uphold a sort of generic Prime Directive, lest Superman For Earth turn into a very different dystopian story, disrupting regular series continuity, damaging the hero’s “good guy” brand, etc.

So, in this novella, Superman is stuck, in ways that productively challenge and critique the genre along with the US way of life. Stern and Gammill’s choice of the first, most iconic, “gold standard” superhero (as opposed to, say, Batman or Green Lantern) reflects their commitment to that task of deconstruction.

Steven Barnes

about the writer

Steven Barnes

Steven Barnes is the NY Times bestselling, award winning author and screenwriter of over thirty novels, as well as episodes of THE TWILIGHT ZONE, ANDROMEDA, HORROR NOIRE and the Emmy Award winning “A Stitch In Time” episode of THE OUTER LIMITS. He is also a martial artist and creator of the “Lifewriting” approach to fiction, and the “Firedance” system of self improvement (www.firedancetaichi.com). He lives in Southern California with his wife Tananarive and son Jason.

Graphic fiction is a sub-set of fiction and as such can handle any genre from romance to horror to philosophy. The question of HOW to do it correctly is certainly important and there is only one rule, one similar to that in cinema and television: Show, don’t tell.

There seem to be two questions here:

- Is it valid to address real-world concerns in fiction? And

- Is graphic fiction fiction?

The answer to the first is that I know of no broadly held social concern that has not been addressed in fiction. My own area of greatest interest, Science Fiction, has been described as a literature that attempts to address one of three questions:

What if?

If Only….

If this goes on…

All three of these are looking at an idea that does not exist, and then connecting to society and human psychology as we understand it (“what if a time machine existed?”) or takes a current trend or problem and extrapolates it into the future and across the horizon (“what if populations continue to increase?”). While classic era SF rarely dove deep into social concerns, the New Wave of the 60’s experimented with both language and thematics, becoming more inclusive and open-hearted.

The success of this approach even in a genre “of ideas” suggests that yes, fiction can handle anything humans imagine or experience, anything they love or fear.

The second question: “is graphic fiction fiction?” would seem to obviously be answered by “yes.” You cannot even ask the question without assuming “graphic fiction” is a sub-set of “fiction.” It is a medium, and can handle any genre from romance to horror to philosophy. The question of HOW to do it correctly is certainly important. I would say there is only one rule, one similar to that in cinema and television:

Show, don’t tell.

Heeyoung Park

about the writer

Heeyoung Park

As a visual artist, I am interested in exploring universal and abstract concepts such as rebirth, freedom, dreaming among many others. Drawing inspirations from deep within, I make art with the hope that my work will serve as a door to a deeper reflection and emotional connection to our true selves and the world we live in.

I don’t think environmental comics need to involve concrete solutions to our problems in order for them to be effective. Can NBS Comics embrace works that do not necessarily include nature-based solutions but have underlying environmental themes and are highly compelling?

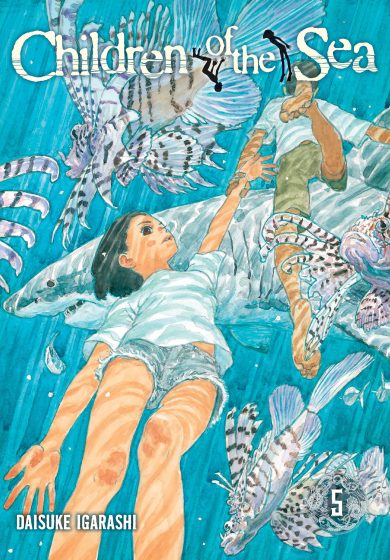

There are different paths that can lead to solving today’s environmental and social challenges, and comics and graphic narratives are definitely an entry point that can attract many people who enjoy visual storytelling. They can be factual or scientific, serving the purpose of educating and informing people, but today, I would like to highlight the visual narratives that have the power to connect us back to nature through emotions and imagination.

You may already be familiar with the works of Miyazaki or Tolkien, so here’s a lesser-known series by Daisuke Igarashi called “Children of the Sea”. In this story, a girl meets two boys who are said to have been raised by dugongs and have supernatural aquatic abilities. She too has a gift of her own—just like every one of us—but it’s the boys, whose names mean sky and sea, who connect her back to the waters and open her eyes to all of its wonders and hidden messages of the universe. “I think the universe is a lot like people.” “At that time, we were part of the sea itself, the universe itself.” These words remind us of the connection that’s been lost to many of us living in a modern society, but it’s the story and art that give life to these messages.

Now, that doesn’t sound like we would learn much about practical solutions to our problems, but an imaginary world like this can really pull us in, touch our emotions and push us to go beyond logical reasoning. That’s where its powers lie. I believe many would be inspired to take action if we could engage more of our emotions and intuition and actually feel that we are part of a bigger world and what that really means. Just like any close relationship, we need both our mind and heart to connect back to nature and rebuild one that’s healthier.

Now, that doesn’t sound like we would learn much about practical solutions to our problems, but an imaginary world like this can really pull us in, touch our emotions and push us to go beyond logical reasoning. That’s where its powers lie. I believe many would be inspired to take action if we could engage more of our emotions and intuition and actually feel that we are part of a bigger world and what that really means. Just like any close relationship, we need both our mind and heart to connect back to nature and rebuild one that’s healthier.

This is why I don’t think environmental comics need to involve concrete solutions to our problems in order for them to be effective. We need different kinds of narratives to engage all people and bridge the gap between humans and nature. So, my question is: Can NBS Comics embrace works that do not necessarily include nature-based solutions but have underlying environmental themes and are highly compelling? If the definition of NBS needs to stay specific for practical reasons, could the two work side by side, and if so, in what form?

This also leads to a more general question: How can we apply both our mind and heart to our current problems and what does that look like?

Emmalee Barnett

about the writer

Emmalee Barnett

Emmalee is a writer and editor with a B.S. in Literature from Missouri State University and currently resides in Spokane, MO. She is currently the editor of TNOC’s essays and fiction projects. She is also the Co-director for NBS Comics and the managing editor for SPROUT: An eco-urban poetry journal.

There are so many different ways to use pictures and written words to paint an enjoyable, informative story. They combine the best parts of a novel and an illustration if you ask me.

I would say yes.

I have been an avid comic reader for several years and have written a few simple comic stories with a couple of different artists as well. There’s something about telling a story alongside pictures that just helps convey the storyteller’s worldview in the most spectacular ways. Other than video, no other narrative style can convey exactly the mental image and emotions the author wishes to plant into the minds of their readers as graphic narratives can.

I personally love how diverse graphic narratives can be in the way of artistry as well as storytelling. There are so many different ways to use pictures and written words to paint an enjoyable, informative story. They combine the best parts of a novel and an illustration if you ask me. Comics are also becoming the new medium of expression amongst the younger generations. Several existing websites, creators, and media are centering themselves around the growing market and uniqueness of graphic narratives such as Webtoons, Tapas, and TNOC’s latest series NBS Comics.

As far as using comics to advance our solutions to social and environmental challenges, I would say comics are the best way to broach those difficult subjects. Comics are a very easy-to-understand approach as far as explaining complicated topics (such as Nature-based Solutions) are concerned. They make the jargon and the graphs and the data more approachable for younger readers as well as older, unknowledgeable readers. The ‘what-if’ genre is always very a compelling way to theorize what would happen to our planet if we don’t do anything, but I believe real-life examples also have a very impactful nudge towards understanding greener solutions. With graphic narratives, we can help those who don’t know exactly how the world will look if we run out of clean water, if the ocean waters rise, if the crops fail, or if the animals go extinct. We can make these broad topics of “climate change” and “extinction” more accessible and break them down into doable solutions for the general public.

Lux Meteora

about the writer

Lucía Sánchez

Lux Meteora (Madrid, 1990) is a visual artist and illustrator interested in the natural world and its kinships. She works with traditional and digital media, developing sequential images that grow into visual storytelling. She is deeply interested in the relationships between species, which she explores through images in poetic, science-rooted pieces.

Comics are quite a good way to share environmental and socially accurate information, packed in small colorful bites. They are able to depict imagery, illustrate points and give a rounding point of view on issues that are sometimes seen as very complex and unsolvable.

Hi, I am Lux. I’m a comic creator, a painter, and illustrator, and I live with fear. I, along with many, sit on my chair every day and face the looming reality of climate change. I see its effects in erratic weather events, prolonged summers, and an extended fire season. I get to draw, research and write about it, and am quite aware that this is the privileged side of things. I also study botany and illustrate other matters, but environmental issues sit under an “urgent” note on top of the table. Developing a Nature-based Solution comic makes me feel that I am adding something good to the conversation, that I am providing accurate information that perhaps the reader didn’t know before. I felt second-hand impact from wildfires and wanted to know more about why they happen and what we can do to mitigate them. This research and its result being out there is something that makes me feel purposeful, in a different way than producing a work of fiction.

Everything, really, has a social and environmental impact. The commerce where we choose to spend our money, the companies we work for, the selection of produce on our baskets, these are all purposefully defining who we want to be, and our consumption has derived, hidden impacts. Reading a good book, a good comic, matters. The content and the purpose matter. Do I want to be a consumer of fast fashion, fast food, fast superhero comics? Are those popular because they are good, or because they are easy to read? Environmentally conscious comics can also be easy to read, can also be visually intricate, and easy on the eyes. That is the goal, and we have the tools for it.

Fanzine culture makes it possible to create a thing and put it out in the world, sharing it without the need to go through editorial bureaucracy. That has aided with creation, and broadened the horizons of artmaking. Digital comics are even more accessible than printed ones, especially those including translations, availing anyone to read them on any device.

As the written word is more and more intertwined with images, as we are constantly subjected to audiovisual overwhelm, text alone provides a weaker impression than text combined with visual media. This does not have to be a sad realization, but a field of possibility.

Comics are quite a good way to share environmental and socially accurate information, packed in small colorful bites. They are able to depict imagery, illustrate points, and give a rounding point of view on issues that are sometimes seen as very complex and unsolvable.

People involved in policy making are not necessarily aware of all the derived aspects of those regulations. Visual storytelling is a tool that provides a different vision, one that can perhaps bring another dimension to the effects of our environmental and social management. Our social and environmental challenges are the biggest thing we face, as a society and as a cluster of generations. I believe in throwing everything we have into that fire, including, of course, our visual stories.

Charlie LaGreca Velasco

about the writer

Charlie LaGreca Velasco

Charlie LaGreca Velasco has worked professionally in the comics industry for 20+years and began at DC Comics, where he emerged as one of the last generation of artists to grace the legendary bullpen before its closure. As a writer and cartoonist, he has created original comics for such companies, from Disney and Nickelodeon to the United Nations. Charlie’s dedication to fostering literacy in socio-economically challenged schools shines through his founding of Pop Culture Classroom, an NGO that harnesses the power of comic books to promote literacy.

In my own experience of creating Environmental Comics for CUNY and the United Nations, I have been fortunate to witness the profound impact these comics can have on our society. However, it has been a process that has taken time and a focused commitment to the project over the course of a decade.

The following statements are made by a derelict cartoonist with no formal schooling whatsoever, other than thousands of wasted hours devouring, reading, and drawing comics.

Comics have enjoyed a small little remarkable run spanning 129 years and are still thriving today. They have firmly embedded themselves in the collective consciousness of various cultures worldwide, evolving into revered institutions, renowned national and global brands, and beloved franchises. Over the hundred plus years of existence they have explored almost every topic, genres, and artistic style—from traditional hand-painted works to digital masterpieces and even today incorporating AI—the power of comics shines through. They offer a universal accessibility and exemplify how this medium can captivate audiences in any genre or style, remaining perpetually relevant as a reflection of the times and places they emerge from.

Comics also possess the ability to weave engaging narratives that resonate deeply with our present-day realities, cultures, crises, and more. These timely stories serve an essential purpose, offering a much-needed platform for those seeking reflections of their own experiences and diverse broad themes that they can relate to. In this way, comics provide a sequential form of literary therapy, facilitating introspection, education, connection, joy, self-expression, and catharsis.